What is Duplex Stainless Steel – Superduplex – Definition

Duplex stainless steel, as its name indicates, is a combination of two of the main alloy types. Duplex stainless steels have a mixed microstructure of austenite and ferrite, the aim usually being to produce a 50/50 mix.

In metallurgy, stainless steel is a steel alloy with at least 10.5% chromium with or without other alloying elements and a maximum of 1.2% carbon by mass. Stainless steels, also known as inox steels or inox from French inoxydable (inoxidizable), are steel alloys, which are very well known for their corrosion resistance, which increases with increasing chromium content. corrosion resistance may also be enhanced by nickel and molybdenum additions. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below which it is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

Duplex Stainless Steel

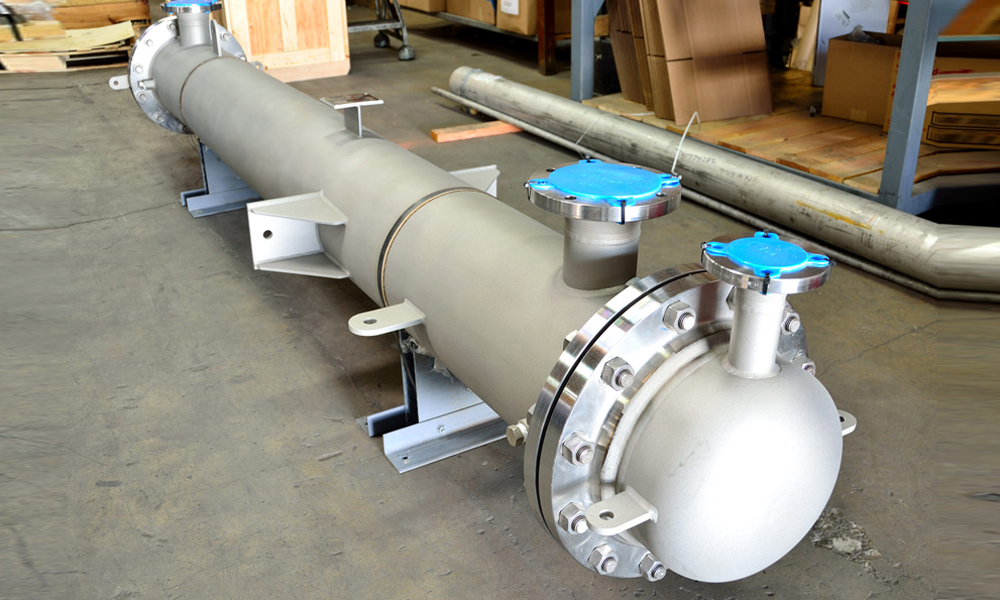

Duplex stainless steels, as their name indicates, are a combination of two of the main alloy types. They have a mixed microstructure of austenite and ferrite, the aim usually being to produce a 50/50 mix, although in commercial alloys the ratio may be 40/60. Their corrosion resistance is similar to their austenitic counterparts, but their stress-corrosion resistance (especially to chloride stress corrosion cracking), tensile strength, and yield strengths (roughly twice the yield strength of austenitic stainless steels) are generally superior to that of the austenitic grades. In duplex stainless steels, carbon is kept to very low levels (C < 0.03%). Chromium content ranges from 21.00 to 26.00%, nickel content ranges from 3.50 to 8.00% and these alloys may contain molybdenum (up to 4.50%). Toughness and ductility generally fall between those of the austenitic and ferritic grades. Duplex grades usually divided into three sub-groups based on their corrosion resistance: lean duplex, standard duplex and superduplex. Superduplex steels have enhanced strength and resistance to all forms of corrosion compared to standard austenitic steels. Common uses are in marine applications, petrochemical plant, desalination plant, heat exchangers and papermaking industry. Today, the oil and gas industry is the largest user and has pushed for more corrosion resistant grades, leading to the development of superduplex steels.

The resistance of stainless steels to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below which it is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

Duplex Stainless Steels – SAF 2205 – 1.4462

A common duplex stainless steel is SAF 2205 (a Sandvik-owned trademark for a 22Cr duplex (ferritic-austenitic) stainless steel), which contains typically 22% chromium and 5% nickel. It has excellent corrosion resistance and high strength, 2205 is the most widely used duplex stainless steel. Applications of SAF 2205 are in the following industries:

- Transport, storage and chemical processing

- Processing equipment

- High chloride and marine environments

- Oil and gas exploration

- Paper machines

Properties of Duplex Stainless Steel

Material properties are intensive properties, that means they are independent of the amount of mass and may vary from place to place within the system at any moment. The basis of materials science involves studying the structure of materials, and relating them to their properties (mechanical, electrical etc.). Once a materials scientist knows about this structure-property correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a material in a given application. The major determinants of the structure of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical elements and the way in which it has been processed into its final form.

Mechanical Properties of Duplex Stainless Steel

Materials are frequently chosen for various applications because they have desirable combinations of mechanical characteristics. For structural applications, material properties are crucial and engineers must take them into account.

Strength of Duplex Stainless Steel

In mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. Strength of materials basically considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. Strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

Ultimate tensile strength of duplex stainless steels – SAF 2205 is 620 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or even to “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Yield Strength

Yield strength of duplex stainless steels – SAF 2205 is 440 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically whereas yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Prior to the yield point, the material will deform elastically and will return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behaviour termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for a low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Hardness of Duplex Stainless Steel

Brinell hardness of duplex stainless steels – SAF 2205 is approximately 217 MPa.

In materials science, hardness is the ability to withstand surface indentation (localized plastic deformation) and scratching. Hardness is probably the most poorly defined material property because it may indicate resistance to scratching, resistance to abrasion, resistance to indentation or even resistance to shaping or localized plastic deformation. Hardness is important from an engineering standpoint because resistance to wear by either friction or erosion by steam, oil, and water generally increases with hardness.

Brinell hardness test is one of indentation hardness tests, that has been developed for hardness testing. In Brinell tests, a hard, spherical indenter is forced under a specific load into the surface of the metal to be tested. The typical test uses a 10 mm (0.39 in) diameter hardened steel ball as an indenter with a 3,000 kgf (29.42 kN; 6,614 lbf) force. The load is maintained constant for a specified time (between 10 and 30 s). For softer materials, a smaller force is used; for harder materials, a tungsten carbide ball is substituted for the steel ball.

The test provides numerical results to quantify the hardness of a material, which is expressed by the Brinell hardness number – HB. The Brinell hardness number is designated by the most commonly used test standards (ASTM E10-14[2] and isO 6506–1:2005) as HBW (H from hardness, B from brinell and W from the material of the indenter, tungsten (wolfram) carbide). In former standards HB or HBS were used to refer to measurements made with steel indenters.

The Brinell hardness number (HB) is the load divided by the surface area of the indentation. The diameter of the impression is measured with a microscope with a superimposed scale. The Brinell hardness number is computed from the equation:

There are a variety of test methods in common use (e.g. Brinell, Knoop, Vickers and Rockwell). There are tables that are available correlating the hardness numbers from the different test methods where correlation is applicable. In all scales, a high hardness number represents a hard metal.